... I would say that Laramie is a town defined by an accident, a crime. We've become Waco, we've become Jasper. We're a noun, a definition, a sign. We may be able to get rid of that... but it sure will take a while.

-- Jed Schultz, in TLP (2001): 9

It actually started out as a game. As I said before, when I started my new life with my husband, we moved about as far culturally as one could get from Laramie, Wyoming: the deep South, so deep South that patches of it are still fighting the "War of Northern Aggression." Culturally, I was an unknown entity to them, and I ended up fielding a lot of personal questions from people who thought that my direct, blunt Western personality was "butch" and not exactly appropriate for a woman. As I met new people and they asked where I was from, I'd count down the seconds in my head until realization struck.

"So, where did you go to college before here, Jackrabbit?" Somebody would ask.People rarely left me disappointed-- if they figured it out at all, they'd make the connection to "that gay kid" Every. Single. Damn. Time. From there came the questions, like, "So, was it really a gay-bashing, or was it just a robbery?" or, "Are the people really that backward and closed-minded out there?" or, "So how many gay people can there be in Wyoming, anyway?" People suddenly felt entitled to ask me much more personal questions, too, like "did you know him?" or, "what was it like to be there?" These questions knotted my stomach and usually went unanswered. My favorite has to be the college student who then decided it was okay to ask me if the "Indians" there still lived on the reservation in tepees. Occasionally I'd get a person who asked me where I'd gone to college, and when I told them, their eyes would get big and they'd say, "Ohhhh," and they'd stop talking. I was already judged.

"Laramie, Wyoming." Then I'd count off the seconds...One Mississippi, two Mississippi, three Mississippi, four...

"Say-- isn't that where that gay kid was murdered?" They said it almost the exact same way every time: that gay kid.

"His name was Matt Shepard," I'd correct them.

After the first year or so, it stopped being so amusing. I was beginning to realize just how much misunderstanding there was surrounding the situation. For instance, a small but significant group of people somehow missed that Phelps was from Kansas, so there was this tendency among people who had read or seen the play to merge Phelps and "The Baptist Minister" in their heads. Naturally, this infuriated me: people were assuming that Phelps spoke for the local community, which he doesn't. Some people were genuinely surprised to find out that Phelps wasn't local, or at least from Wyoming. When communities in the South started having their own encounters with Phelps and his slavering entourage of media harpies-- at soldiers' funerals, and during the coal mine disaster-- I stopped getting those questions.

But the play itself was something I also kept bumping into. When I went to the 2000 Laramie performance of TLP, the members of Tectonic Theater had a short Q & A session with the audience afterwards. One woman (it might have been Marge Murray, I'm not so sure now) complimented them on their performance and said, "This isn't so much a play as an anthropology project." She then expressed some concern about what would happen when other people, play companies who hadn't met the Laramie residents and developed a level of sympathy for them, started performing the play. My memory is a little fuzzy at this point. "You're not going to publish this so others can perform it, are you?" I remember someone asking, and Moisés Kaufman squirmed a little on the stage. Then he dodged the question. Maybe he wasn't sure about how he was going to finesse that question enough to admit to that theater full of Laramie residents and his own interviewees that they were going to do exactly that.

The Vintage edition of the play was released early in the fall of 2001, and by the time I started college in the fall, some professors were already assigning it for classes. I was wandering through the bookstore looking at titles when I saw copies of the play sitting on a shelf. An acquaintance of mine came alongside me as I stared, gape-mouthed, at the cover.

"Jackrabbit, what's wrong?" she asked me. I thrust the book at her.Okay, so obviously I overreacted. (I'm really sorry, Mr. Kaufman.) I thought so too, as soon as I had enough time and distance to cool down. But that outrage I felt was real, and it had a source. After the TT performance the previous year, I finally was able to give Tectonic the benefit of the doubt: they weren't like the national reporters. They weren't just here for an easy story and a fast buck; they actually cared about the people they were portraying. Realizing that they had just broadcast The Laramie Project like ragweed seed over the whole country made me feel like I had been duped. If they actually cared about how Laramie looked to the rest of the world, I thought, then why the hell would they let anybody do as sloppy and irresponsible of a performance as they pleased? What was going to happen when a play company full of haters got hold of this book and decided to have a production?

"This is what's wrong," I hissed. She gave me a confused look.

"Moisés Kaufman is a greedy, money-grubbing bastard," I snarled, and I stomped out.

As I got a little more perspective, however, their publishing the play made more sense. Why wouldn't they want to publish this thing? I reasoned. Why wouldn't they? If you understood their social and political aspirations for the play, then publishing the thing was a no-brainer. And once the script was released, that's what happened: productions started sprouting up all over the US, and people started talking. And protesting. And thinking. Of course they were going to publish it. But that didn't make it sting any less to realize that I had absolutely no control over what people were going to see, and how they'd react.

That little nightmare came true in pretty short order. An independent acting company in my college town sponsored a production of the play pretty quickly. When I read an article on the play in the newspaper, I started to feel sick. There was a lot of talk in the article about what "those people" are like, judgmental language about Laramie that smacked of elitism. The actors in the dress rehearsal photo were all wearing terrible polyester Western shirts from the seventies that they must have culled from the vintage clothing shop downtown. I threw away the newspaper, infuriated, and waited for the questions to come after the performance. And those questions did come: "So you used to live in Laramie? Can I ask you something...?" The 20/20 special that came out a few years later only added fuel to the fire, which meant I spent an inordinate amount of time in the Deep South seemingly defending myself from a stereotype that the media created, but one that the controversy around The Laramie Project fomented.

I resented this fact immensely. I mean, Laramie was my adopted home, not theirs, and let's face it-- a large part of my identity is tied to the land, which means that I am, at least in part, a land stained in the blood of Matthew Shepard. Over time, I've learned to accept this fact, but back then it hurt; it hurt so badly to be judged like that that, like many so many others in psychological pain, I wrongly blamed the messenger. Tectonic Theater didn't have to walk down the street among people who looked at me with minds full of gay-bashers and buck fences and hate; I did. So after a couple years, my reflex response whenever questions arose was to rip the play to shreds and tell people about how inaccurate it was. That doesn't mean I was justified in what I did. It just means that there was a reason that I did it.

So, that was my life for a long time. After five years of fielding those questions at my college town in the deep South, I moved to the not-so-deep South to start a PhD program in 2006. It was a fresh start, a new location, and I was genuinely excited to get moving down the path towards my degree. We had graduate student orientation the week before classes, where we introduced ourselves and did workshops to prepare for teaching our English classes.

During one of our orientation sessions, one of the RWL professors informed us that there were a lot of cultural events we might tie into our classes that semester. "For instance," she said, "the Theater Department will be doing a production of The Laramie Project this fall that could tie in well with your classes..." I felt like I had just been kicked in the liver. I hunched over and groaned while my head swam, and one of the new lecturers nearby gave me a concerned look. "Are you okay?" She whispered. I shook my head and fought back the nausea. As I held my breath to keep from throwing up, I remember feeling rather stupid. It didn't matter where I went, this damn play was following me and I couldn't let it define my life any longer.

So, with a lot of fear and loathing (and a little bit of encouragement from that RWL professor) I decided I'd teach the play to my freshmen as a way to help me get over the panic. I discovered that reading the play was actually manageable, so I figured that maybe that the panic and terror I felt when I saw the 2000 version was finally over. I taught the play, at first, as a cultural study with a clear purpose, and we spent a lot of time first by making a character sketch of the Laramie community and then connecting ideas and sentiments made by Laramie residents with the culture at large. How can we see Laramie asking the same questions and engaging in the same debates about class, homosexuality and tolerance that we see on our campus? I'd ask them.

So, with a lot of fear and loathing (and a little bit of encouragement from that RWL professor) I decided I'd teach the play to my freshmen as a way to help me get over the panic. I discovered that reading the play was actually manageable, so I figured that maybe that the panic and terror I felt when I saw the 2000 version was finally over. I taught the play, at first, as a cultural study with a clear purpose, and we spent a lot of time first by making a character sketch of the Laramie community and then connecting ideas and sentiments made by Laramie residents with the culture at large. How can we see Laramie asking the same questions and engaging in the same debates about class, homosexuality and tolerance that we see on our campus? I'd ask them. Let's be honest: part of the reason I wanted to teach the play was so that I could control the conversation for once. Instead of putting me on the defensive like I was used to, my students were more open, more curious than anything. These students came from a more rural and agrarian background than where I was before, so they could identify with the community. I was so relieved that I could let them draw their own conclusions without feeling completely judged by what they came up with. We could talk openly about the more intolerant opinions in the play without them assuming that they spoke for me personally. And I discovered, with a little bit of distance from the text, that I had been unfair about what the play had to say about Laramie.

But there was still that fall production to deal with: I had been ignoring it. The reviews looked pretty good, to be honest, and a few of my students wanted to see about going, so I bit my lip and walked over to the theater office to find tickets. The venue was a small lab theater, so they were completely sold out; I had to wait around on the last night of the show hoping for an unclaimed ticket. Fortunately, a few people never bothered to show up, so on November 19 I was one of about five people able to squeeze in just before the curtain call and watch my second performance of The Laramie Project in Appalachia.

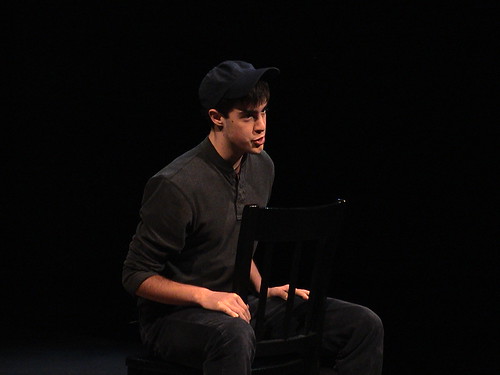

The theater space was small and intimate. It was an undergraduate production and well acted; the kid playing Jed Schultz (left) reminded me so much of Jed it was actually a little bit scary. The girl playing Romaine had a solid, convincing performance; it just wasn't remotely like the Romaine I knew from high school. When all you have are a person's words, I realized, how do you read their character? She gave a great performance, but it was Romaine as a character rather than how Romaine Patterson really was.

But then we got to Act II again, and that insane "media descent" moment in "Gem City of the Plains." There were no live televisions dropping from the ceiling this time, but the actors all pulled out their fuzzy microphones and overlapped their testimony to make that same wall of noise. This time, I felt terror like a jackboot slam in between my shoulder blades and I almost choked on a flood of incoherent panic. I covered my eyes and sobbed. The problem was that I couldn't cover my face and my ears at the same time. At the intermission I had to lock myself in a bathroom stall to try to stop hyperventilating. By the time they dimmed the lights for the end of intermission I was reasonably stable enough to go back, and I went back to my seat with red eyes and shaking hands. This was a bad idea, you see, because I had completely forgotten about Fred Phelps at the beginning of Act III.

The kid who played Phelps was a taller, wiry fellow who fit the type well, and he stalked over the stage menacingly while he gave his lines. Whoever did the costume for Phelps had done their homework, too: he was dressed in a similar windbreaker and cowboy hat Phelps wears everywhere, and he had a placard in each hand. The flash of white when he hoisted the signs was the trigger this time. The panic seized me by the throat, and I cried so hard that my whole body was shaking. I had my hands over my face for most of the rest of the play, and I was an utter wreck when it was done.

So, that was my second TLP viewing experience, and in a lot of ways the trauma was so much worse for the 2006 showing than six years previously. The TT production was so much closer to the actual event, and it was staged and acted with devastating accuracy. So why did I freak out so much worse six years later, at an extremely well done but nevertheless undergraduate performance? Because I was no longer in Laramie, in a safe environment? Was it six years of frustration and repression of the event itself? Or, was it other personal issues going on at the same time?

Or, was there something about the lack of accuracy to people and events that I knew that made the experience so much more damaging? I don't really know how to answer all that. All I know is that for the next three years I'd spend my time teaching this play to every English class I taught, considering these questions, and especially trying to figure out how to translate the questions I was having about my own engagement with the social issues of the play into my lived existence.

PHOTO CREDITS:

1) "Haunted" churchyard from the Southeastern US, from slworking2's Flickr photostream:

We used to give ghost tours here back in the day when I worked for a tour guide company. The stories we told here are simply not true... but they are fun.

2)Westboro protests in Burbank, California, 2008, from k763's Flickr photostream:

But then we got to Act II again, and that insane "media descent" moment in "Gem City of the Plains." There were no live televisions dropping from the ceiling this time, but the actors all pulled out their fuzzy microphones and overlapped their testimony to make that same wall of noise. This time, I felt terror like a jackboot slam in between my shoulder blades and I almost choked on a flood of incoherent panic. I covered my eyes and sobbed. The problem was that I couldn't cover my face and my ears at the same time. At the intermission I had to lock myself in a bathroom stall to try to stop hyperventilating. By the time they dimmed the lights for the end of intermission I was reasonably stable enough to go back, and I went back to my seat with red eyes and shaking hands. This was a bad idea, you see, because I had completely forgotten about Fred Phelps at the beginning of Act III.

The kid who played Phelps was a taller, wiry fellow who fit the type well, and he stalked over the stage menacingly while he gave his lines. Whoever did the costume for Phelps had done their homework, too: he was dressed in a similar windbreaker and cowboy hat Phelps wears everywhere, and he had a placard in each hand. The flash of white when he hoisted the signs was the trigger this time. The panic seized me by the throat, and I cried so hard that my whole body was shaking. I had my hands over my face for most of the rest of the play, and I was an utter wreck when it was done.

So, that was my second TLP viewing experience, and in a lot of ways the trauma was so much worse for the 2006 showing than six years previously. The TT production was so much closer to the actual event, and it was staged and acted with devastating accuracy. So why did I freak out so much worse six years later, at an extremely well done but nevertheless undergraduate performance? Because I was no longer in Laramie, in a safe environment? Was it six years of frustration and repression of the event itself? Or, was it other personal issues going on at the same time?

Or, was there something about the lack of accuracy to people and events that I knew that made the experience so much more damaging? I don't really know how to answer all that. All I know is that for the next three years I'd spend my time teaching this play to every English class I taught, considering these questions, and especially trying to figure out how to translate the questions I was having about my own engagement with the social issues of the play into my lived existence.

PHOTO CREDITS:

1) "Haunted" churchyard from the Southeastern US, from slworking2's Flickr photostream:

We used to give ghost tours here back in the day when I worked for a tour guide company. The stories we told here are simply not true... but they are fun.

2)Westboro protests in Burbank, California, 2008, from k763's Flickr photostream:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/26806952@N08/ / CC BY 2.0. Posted without comment.

3) Book on a shelf, by me.

4) Poster from the 2006 production I had attended during my first year of grad school, picture by me. It's interesting-- the map overlay they have on the poster includes my hometown, where I graduated high school from.

5) Laramie Project 37, originally uploaded by rogerchoover. Photograph of the performance, with the actor playing Jed Schultz reading his first lines as that character.

3) Book on a shelf, by me.

4) Poster from the 2006 production I had attended during my first year of grad school, picture by me. It's interesting-- the map overlay they have on the poster includes my hometown, where I graduated high school from.

5) Laramie Project 37, originally uploaded by rogerchoover. Photograph of the performance, with the actor playing Jed Schultz reading his first lines as that character.

No comments:

Post a Comment