One evening while I was in Laramie, I meet Coyote for dinner, and he walks me over the catwalk towards his home. He wants to show me West Laramie's green belt project, a paved walkway following the river on the south end. He wanted me to see how pretty it all is in the sunset, he said, and maybe we can get some pictures with my camera. (It was beautiful, too. It's a shame the light didn't hold.) Maybe we'd see some badgers down by the southern loop, he adds. They live near the prairie dog town where the pickings are easy. Sometimes he comes down there to just sit and watch, to see if he can catch a glimpse of their stripey heads poking out of their dens.

As we stroll down South Pine and pass through other streets on the way to the green belt, he points out the houses of people he knows who live there: police officers, professors, health professionals. We turn a corner and pass by one small, well-kept house with picket signs for both candidates in the current election for sheriff, which makes no sense until we see the current Sheriff's cruiser parked in the driveway. We both laugh; local politics can be funny that way. He also points out a beautiful old church just beyond the tracks in the other direction, with a white steeple glowing in the dusky light. He tells me it's the second-oldest church in Laramie-- "and it's in

West Laramie," he adds with a touch of pride.

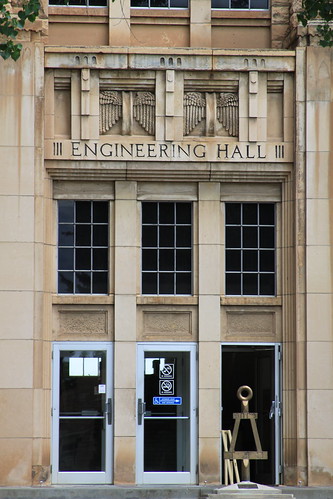

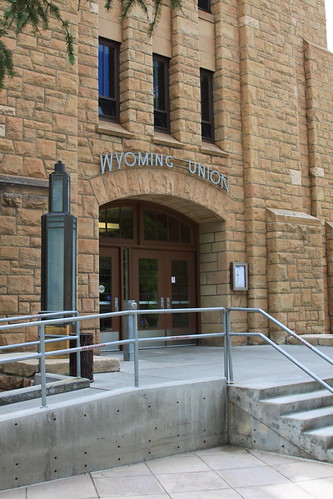

And it occurs to me, as I listen to Coyote talk animatedly about his neighborhood, that if I ignore the university, West Laramie doesn't look any different to me than the rest of the town. In the sunset I see the same wide paved streets on East Garfield as West Garfield, arched by the same massive, shaggy cottonwood trees; they have the same small, older houses on either side. If the railroad tracks weren't there to aid the imagination, in all truth, the difference between the two sides would be difficult to discern, and the only real details I can see between East and West are the tall, Victorian mansionettes on the east side, the cookie-cutter subdivisions north of campus, and a few old, tattered storefronts converted to residences in West Laramie. Even West Laramie's trucking district near the I-80 exit has its equivalent on the other side of town, and the east has its own ramshackle, gentrified houses with absentee landlords just two blocks away from the university. If this little district weren't living in the shadow of its more cosmopolitan neighbor, West Laramie could be any small town in Wyoming which has changed its appearance with shifting fortunes: Afton, Pinedale, Saratoga, Shoshoni.

"For most of the people who live here, it's not about being rich or poor," Coyote explains. "It's about choosing where you want to live. For a lot of people, West Laramie is convenient, or it's quieter, or they don't want to live anywhere near the campus. Hell, my landlord

works on campus, and he lives out here," he adds with a grin.

For someone barely scraping by and renting an apartment he once described as a " convenient rat-hole," Coyote speaks quite defensively for West Laramie. He speaks of this place as home. They have the green belt, he points out, and some of the best and most underused parks in the city. "Come on-- what can be better than a place called 'Optimist Park?'" He quips. He grins in the darkness.

But it's the defensiveness in his voice that interests me at the moment. "So, do you get the sense there's still a stigma to living in West Laramie?" I ask him. He scowls at me in the growing darkness.

"But it isn't true," he says.