Being the Final Grievance (hooray!) Against Tectonic Theater

During this Festivus Season

I was having a conversation a while back with an acquaintance of mine who also studies The Laramie Project. Dr. F, as I'll call her, is this beautiful, crazy, wonderful, innovative rhetoric and composition professor in our department, and she's a theater fanatic on the side. Our chat eventually wandered over to Angels in America, a play which we both love, and she started talking about staging.

I was having a conversation a while back with an acquaintance of mine who also studies The Laramie Project. Dr. F, as I'll call her, is this beautiful, crazy, wonderful, innovative rhetoric and composition professor in our department, and she's a theater fanatic on the side. Our chat eventually wandered over to Angels in America, a play which we both love, and she started talking about staging."One thing I've noticed about American theater right now," she told me, "is that most directors don't seem to trust their audiences as much as those abroad." I had to ask for clarification on what she meant. "Well, take the Central Park encounter in Angels," she responded. "When I was studying in London, I saw a production where the two actors in that liaison were on opposite sides of the stage. They just trusted the audience to make the connection about what's going on without having to stage the action with each other or even act it out. It made that moment of sex look as disconnected and lonely as it really was." Having seen the Laramie production of Angels, I could really see her point, where that sexual encounter was enacted on a platform between the actor playing Louis and Jed Schultz.

"Most of the plays I saw in London played fast and loose with the directing, which opened up the stage to all sorts of new possibilities," she continued. "But that meant that they had to lean on the audience to make the connective leap. I really haven't seen a lot of theater here in the States that is willing to trust their audiences quite like that."

Trusting the audience. Although I'm a little on the fence about her judgment of American theater, I've been mulling those words over for quite a while now. What's more, I think I'm starting to see a connection to that idea with some of the aesthetic differences I have with The Laramie Project. As I've been working through my "Airing of Grievances," I've started to notice a few patterns; sure, I have problems with the structure of the play and how the concept relates to Laramie as both a community and place, but there's something else here, too, that has more to do with the structure of the play itself.

I think that maybe 1) these people are incredible, brilliant, and talented writers with a clear interest in dramatic form, and 2) these form-driven dramatists are afraid to trust their audiences too much with the factually ambiguous story of Matt's murder. Perhaps, Tectonic wants to tell a story of cause/effect through Laramie's voices, but the narratives we have don't lend themselves to it, and the only way to get their voices to tell that cause/effect story is to push them that way. This problem of overworking, strangely, has an element of narrative and truth to it, too: Tectonic's willing to let narrative drive most of their play, so long it never gives any doubt about the forensic facts of the murder, of the cause and its effect. A fear about the fragility of forensic truth might be forcing them to heavily edit the narrative truth.

And so, I hereby submit my final charge against Tectonic Theater regarding their production of The Laramie Project and 10 Years Later, which I guess isn't really a bad thing at all:

#4: Trying Too Damn Hard

Maybe this is just a difference of aesthetic taste on my part, and on that note, failure to meet the needs of my literary palate shouldn't really be a grievance per se. Nevertheless, it's a concern I want to discuss.

Okay, so I know I keep wandering back to South Africa's apartheid past and the TRC whether it fits or not, but hey, it's the only analogue to narrative and determining truth I can comfortably speak about. So, here goes...

Even though the [Truth and Reconcilaton] report offers a good exposition of different concepts of truth, especially of factual truth and narrative truth and then of social or interactive truth, the distinction is not sustained. In arriving at findings, all is accepted as evidence, an ingredient of the factual truth. If we ignore the frame of our various dispositions through which evidence reaches us, we lose the context of the multiplicity of truth, both in dimension and in perspective. Truth, reconciliation and national unity can only be understood within the concept of multiple truths...

TRC executive member Wynand Malan didn't win a lot of praise for writing this minority report on South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission's findings (actually, he was called callous and insensitive to the victims giving testimony), but regardless of whatever frame determines his own perspective on truth, he has a point. Experiential, narrative testimony treads an uncertain path alongside narrative truth, forensic truth, and myth, and many of us are uncomfortable with that concept.To pour history into a mould is to recreate the potential for conflict which our Constitution and politics since 1990 have largely removed. A shared understanding of our history requires an understanding of different perspectives, not the building of a new national myth. Presenting 'the truth' as a one-dimensional finding is a continuation of the old frame.

--Wynand Malan,

TRC South Africa Report Minority Position, sec. 27

Although Malan really wants for these kinds of truth to be easily separated and he criticizes the Commission for not maintaining that clean line between them, that's impossible; for they inhabit the same mnemonic space. In contrast, Tectonic seems more aware of this strange situation of memory-- that forensic truth in Matt's death is built, not as a part of objective reality, but from layers of different narrative truth which often contradict one another. In this sense, I might say that Tectonic has a leg up on Malan, who was struggling through these same issues as the Commission wrote its report.

What Malan realizes that Tectonic does not, however, is that when one "pour[s] history in a mould" to replace a previous, bad history, you're not understanding the truth or history or whatever you want to call it. You're just replacing one monologic narrative of history with another, and that fuels rather than defuses cultural tension. This is the question-- the motives and details of Shepard's murder-- that Tectonic seems the most anxious about: one story must displace the other rather than coexist; they must struggle in dialectic.

Why so much concern, Tectonic? I have a guess (which is probably wrong) but I believe that the social power of Tectonic's play-- what the TRC would call its social or interactive truth-- lies in laying bare the voices of a community trying to come to terms with an unthinkably horrific act of homophobic hate. Tectonic seems to think that a clear cause and effect-- Matt was killed specifically because he was gay-- is an essential backdrop for the conversation that follows. For that reason, the play never really lets us doubt for even a second that Matt's death occurred because he was gay. They allow doubt and angst of uncertainty charge the play in so many other places, but it cannot dwell here.

I really don't think that such a clear cause and effect is really necessary. The important thing is that, after Matt's murder, people start talking about homophobia and where it comes from, whether or not the "gay panic" defense, the robbery motive, or the hate crime angle are "really the truth." I feel like that most good audiences can make that connection without having to be spoon-fed the "right" answer.

So, that's where I think this all comes down to an issue of audience trust. Tectonic is willing to tell us in detail about what happened to Matt over the hours he was brutalized and abandoned, but they seem to be afraid of giving the impression that Matt's death could be anything but an out-and-out hate crime. They're afraid of letting the audience decide if if the Baptist Minister's callous dismissal of Matt Shepard is "the seed of violence." Tectonic Theater's editing choices trust the audience with a lot of difficult things, like synthesizing the disparate voices, dealing with multiple reactions to his murder, and even handling the raw-edged grief of his friends and family onstage. They want the audience to live in an ambiguous realm of multiple stories, but they seem much more afraid to do let the audience dwell in an ambiguous realm of facts.

Don't get me wrong-- this criticism comes as someone who doesn't doubt for even a moment that Matt's murder was a hate crime. And yet, I'm also someone who believes that the forensic truth behind the murder has been lost to memory.

If I'm going to say that a multi-narrated play representing an entire town through the voices of almost 70 people has been over-edited and monolithic, I sure as heck better put my money where my mouth is. For that reason I would like to walk you through two examples: the Fireside and the religious moments in Act 2. Let's start with the moments at the Fireside to give us a good place to start.

1. Modus operandi

MATT GALLOWAY: [...] And I remember thinking to myself that I'm not gonna ask them if they want another [beer], because obviously they just paid for a pitcher with dimes and quarters, I have a real good feeling they don't have any money.

ROMAINE PATTERSON: [...] They can say it was robbery... I don't buy it. Not even for an iota of a second.

MATT GALLOWAY: Then a few moments later I looked over and Aaron and Russell had been talking to Matthew Shepard.

KRISTIN PRICE: Aaron said that a guy walked up to him and said that he was gay, and wanted to get with Aaron and Russ [...] They wanted to teach him a lesson and not to come on to straight people.

MATT GALLOWAY: Okay, no. They stated that Matt approached them, that they came on to them. I absolutely, positively disbelieve and refute the statement one hundred percent [...] Bullshit. He never came on to me. Hello?!? He came on to them? I don't believe it [...]

ROMAINE PATTERSON: But Matthew was the kind of person... like, he would never not talk to someone for any reason [...]

PHIL LABRIE: Matt did feel lonely a lot of times. Me knowing that-- and knowing how gullible Mat could be... he would have walked right into it. (30-31)

In this passage you can see a pretty complicated tennis match going on in the middle of Matt Galloway's narrative of Matt's final hours. For some reason, his full testimony can't just stand alone as a firsthand account from the last person to see Matt alive; it has to be put into a different context, within a different story frame, so that the audience isn't misled about McKinney and Henderson's MO. He has to have a conversation with others to make it clear that both the robbery motive and the "gay panic" defense aren't true.

In this passage you can see a pretty complicated tennis match going on in the middle of Matt Galloway's narrative of Matt's final hours. For some reason, his full testimony can't just stand alone as a firsthand account from the last person to see Matt alive; it has to be put into a different context, within a different story frame, so that the audience isn't misled about McKinney and Henderson's MO. He has to have a conversation with others to make it clear that both the robbery motive and the "gay panic" defense aren't true.The first issue comes with Galloway's recollection of the murderers being broke, which you can see above. At this point, Tectonic breaks up Galloway's narrative to insert Romaine's testimony about Matt's generosity and her denial that the motive was robbery. Even though Matt Galloway is a trustworthy figure overall, Tectonic didn't want to let this statement go by unanswered, and so Romaine speaks here to fill in the gap. Was that even necessary? Maybe it was, or maybe not.

Next, look to Kristin Price's statements which immediately follow when Galloway notices the two suspects talking to Shepard. What were they talking about? Only McKinney and Henderson really know, of course; so, Kristin Price tells us what Arron told her-- that Shepard made sexual advances, and that they planned to rob him in response. Now Galloway gets to step in and refute Kristin's version of events: "They say that Matt approached them, that he came on to them. I absolutely, positively disbelieve the statement one hundred percent" (31). Galloway refutes both claims fairly handily, especially since Matt was the one sitting at the bar and they were the ones wandering around beforehand.

But if Galloway is right, why would Shepard even talk to them? And why would he leave the bar with them? The last two statements, from Matt's friends Romaine and Phil Labrie, answer the question for us: Shepard was too friendly for his own good. He was gullible. And whatever these two proposed, a sweet, clueless fellow like Matt Shepard "would have walked right into it." The end of the Moment comes when the DJ, Shadow, sees them leave with Matt and he claims, "I didn't figure them guys was gonna be like that."

What would have happened if these voices spoke on their own, without interrupting or refuting each other? Would the audience get the "wrong" idea? I don't know how to answer that. But the one thing we have to keep in mind is that, out of all these different narratives of what happened at the bar, none of them knows the truth. What we have are different stories, speculations based on different kinds of experiences. Matt Galloway was there, but he didn't hear what was going on. Romaine and Phil knew Matt Shepard extremely well, but they weren't there. Kristin Price heard it straight from Aaron McKinney's mouth, but neither she nor McKinney are trustworthy. In the face of this, Tectonic weaves their accounts together in such a way that discredits any motive that would suggest that Matt's murder wasn't a hate crime. What they don't do is allow these different perspectives combine to give us a glimpse at the truth. They edit these testimonies, vaguely like the TRC did, into a report.

So, how much does Tectonic's "history in a mould" change how an audience might read these lines? Let's try shuffling around some other voices to see what we might have gotten...

MATT GALLOWAY: [...] And I remember thinking to myself that I'm not gonna ask them if they want another [beer], because obviously they just paid for a pitcher with dimes and quarters, I have a real good feeling they don't have any money.

JEN: Aaron's done it before. They've both done it. I know one night they went to Cheyenne to go do it and they came back with probably three hundred dollars. I don't know if they ever chose like gay people as their particular targets before, but anyone that looked like they had a lot of money and that was you know, they could outnumber, or overpower, was fair game (60-61).

MATT GALLOWAY: Then a few moments later I looked over and Aaron and Russell had been talking to Matthew Shepard.

KRISTIN PRICE: Aaron said that a guy walked up to him and said that he was gay, and wanted to get with Aaron and Russ [...] And Aaron got aggravated with it and told him that he was straight and didn't want anything to do with him and then walked off. He said that is when he and Russell went to the bathroom and decided to pretend they were gay and get him in the truck and rob him. They wanted to teach him a lesson and not to come on to straight people.

Does the structure of these voices matter? Yes. That whole stupid, ugly rewriting I just did relies on the subtraction of a single voice and the addition of another. Now imagine that "moment" with some mention that Aaron McKinney was in trouble for robbing a KFC, and you'd have the hate crime deniers drooling all over themselves in excitement. My new, edited frame, however, is just as forced, just as misleading as what Tectonic did. Neither frame for these narratives can claim to be the truth, for truth comes only in considering multiple perspectives, not weeding them out.

As Wynand Malan had said before, "If we ignore the frame of our various dispositions through which evidence reaches us, we lose the context of the multiplicity of truth, both in dimension and in perspective." Tectonic has provided a very clear frame through which these stories reach the audience, and it's one which doesn't let the audience decide for themselves that, when you sift though all these perspectives, a homophobic man killed Matt because he was gay, and a friend of his helped.

If these voices were just allowed to talk on their own instead of talk back and refute, I now feel confident that the audience would still have the same revelatory and socially-charged response to The Laramie Project that they do now. Maybe, even, the play would have gotten less pushback for "forcing" a specific perspective on their viewers, as the haters have claimed. Perhaps, however, since I'm not a playwright myself, I just have too much faith in a playgoing audience to wrestle through these issues seriously after they walk out of the theater doors.

* * *

2. Seeds of Violence

For this example, I'd just like to give you a list of short moments leading up to Matthew Shepard's death in the hospital:

1. Two Queers and a Catholic Priest: Father Roger explains that homophobic and hateful language against gays and lesbians is "the seed of violence."

2. Christmas: Andrew Gomez and Aaron McKinney talk about why he murdered Matt Shepard over Christmas dinner-- in jail. McKinney says that Shepard came on to him.

3. Lifestyle: The Baptist Minister says he will work for McKinney's salvation, as Shepard is now beyond all help. He says that he hopes Shepard had a moment before death to repent of his "lifestyle."

4. That Night: Shepard's condition worsens, and he dies at the hospital.

5. Medical Update: Rulon Stacey reads the press announcement of Matt Shepard's death.

6. Magnitude: Stacey admits to "losing it" and bawling on live television; he then recounts receiving, among many e-mails of support, a very hostile message: "Do you cry on TV for all of your patients or just the faggots?" Stacey describes his shock at the message, noting, "I guess I didn't understand the magnitude with which some people hate."

7. H-O-P-E: Tectonic departs after their second visit, and Doc Connor says that Matthew wouldn't have wanted his killers to die.

(end of Act 2)

In The Laramie Project, most of the religious opinions in the play are intended to all stitch together for a simple point: to reinforce the idea that McKinney and Henderson's religious influence had a lot to play into their actions, and that those influences are the major religious traditions in the town. From Johnson's opening comments that Baptists and Mormons are "like jam on toast" to Father Roger's insistence that hateful words against gays are "the seed of violence," all these statements are carefully stitched together to come together to a single phone call where The Baptist Minister acknowledges his connection to one of the murderers and condemns Shepard in the same breath. This is something that Stephen Wangh noticed and commented on as well when he pondered Tectonic's focus on the religious narrative and the nature of forgiveness:

In the play, we hear [The Baptist Minister's] unsettling sentiments right after listening to Father Roger tell two theater company members that, in his opinion, calling homosexuals names is the seed of violence [Kaufman et al., 2001, p. 65]. So we understand that the Baptist minister’s homophobia is just such a seed of violence. The point is driven home in the last act when an antigay activist, the Reverend Fred Phelps, comes to picket and to preach outside the funeral of Matthew Shepard, carrying a sign that reads God Hates Fags. (Wangh 2005, p. 13).Not surprisingly, I tend to agree with Wangh. While it is very neatly done, and certainly the sign of some amazingly well-scripted work, it's not exactly letting each person's narrative speak alongside one another. To reiterate, we have to be aware of the "frame of our various dispositions through which evidence reaches us."

The trajectory of these voices runs as follows: we start Act 2 with Matt Shepard in the hospital. At the point of the "Two Queers" moment, Tectonic uses Father Roger's conversation to set a clear cause and effect: hateful speech against the LGBT community is a "seed of violence" and leads to real violence later. We then see Gomez and McKinney sharing a few "seeds of violence" over Christmas dinner as they talk crudely about Aaron's victim. Their homophobia comes out over a meal on a Christian holiday. We see a clear, but coincidental, connection between faith and violence in this moment. But we don't know one very important thing: where did he learn it from?

The next moment, with the Baptist Minister, answers that question for us-- McKinney was a visitor to the church, and his girlfriend was a member. Then we hear similar statements from McKinney's "pastor," so we are led, showing the legacy of this seed of violence from minister to congregant. We immediately switch to the moment of Matthew's death, and more seeds of violence spewed at Rulon Stacey afterward. The seed of violence and the end result of that violence follow in very quick succession; we see the extreme damage that violence does when Shepard dies, and we see those same seeds of violence planted again with the anonymous email. The audience sees a clear cause and effect.

That cause and effect is on a theatric level, but is there really? Let's put these moments back in their original contexts and consider their individual circumstances. Father Roger's warning about the "seeds of violence" is originally directed at Tectonic Theater, not others:

"Do you realize that is violence? That is the seed of violence. And I would resent it immensely if you use any thing I said, uh, you know, to-- to somehow cultivate that kind of violence, even in its smallest form. I would resent it immensely. (66)Father Roger's bringing this statement about language up because he's afraid of being taken out of context, not only because he is opposed to hate speech. And he labels violent speech and hate-speech the kind of thing he most dreads and would most resent being applied to him.

Now look to The Baptist Minister, and strangely enough, that is exactly what Tectonic does to him. Granted, TBM is a blunt, unlikable fellow with unsavory thoughts on same-sex desire, but there's no reason to think that Father Roger would label TBM's preoccupation with "living right" and Matt's "lifestyle" in connection with his concern for his salvation should be labeled the seed of violence; however, the proximity of the two statements makes the connection for us. But what did Father Roger say the seed of violence was?

...you know, every time you are called a fag, or you are called you know, a lez or whatever...Father Roger might intend a lot of things being the seed of violence, but he was referring here to verbal attacks. TBM is referring the need for salvation, not just for a gay male, but for Aaron McKinney and Kristin Price as well, whom TBM would also say were suffering from issues of "lifestyle" (they had a kid out of wedlock and lived together). Andrew Gomez and Aaron McKinney, we see, are guilty of that kind of verbal violence, as is the e-mail attack on Rulon Stacey. But would Father Roger say that, since Rulon Stacey doesn't "agree" with the homosexual "lifestyle," that he is guilty of the seed of violence as well? That's where I hesitate. It's the same generalization the audience is being asked to make about the difference between Father Roger and TBM even though their denominations' doctrinal stances on homosexuality aren't that far apart.

LEIGH FONDAKOWSKI: Or a dyke.

FATHER ROGER: Dyke, yeah, dyke. Do you realize that is violence? That is the seed of violence. (66)

Father Roger sets out a clear cause/effect we can see in "Christmas" and "Magnitude," and the medical moments and the end of Act 2 drive home the very real consequences of that violence. But since TBM has to speak into this specific context rather than simply the context of the original conversation, he is specifically named as the source of Aaron McKinney's real violence on Matthew. It's a matter of the cum hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy: just because certain conditions occur in tandem with an event doesn't mean that one caused the other. They may be completely unrelated. But this sequence of events, which mimetically reproduces the seed, dissemination, and fruit of violence together, doesn't let the audience consider them as discrete narratives with their own perspectives. What we're seeing is the result of Tectonic's historical mold pressed over Laramie's voices to make religion the main source of homophobia.

So, in short, I think they could have made this narrative a hell of a lot more complicated by just cutting loose and letting the audience struggle with these voices without providing a clear answer like they did. Make them uncomfortable, Tectonic. Blow our minds; allow us to be confused. Trust your audience enough to make those same amazing leaps of intellect that we see in some of your interviewees. Just as they grappled with this event and were confused, challenged or inspired... your audience needs to feel that, too, they need to mimetically process these disparate voices and feel that same ambivalence so they can take it into the real world. Such is the very point of the kind of theater that you produce, and it is important. I want you to make this leap because what you do is so important to all of us.

So, is this necessarily a "charge," to say that Tectonic just worked too damn hard to try and steer this giant mess of a story? In one sense, not really, I think. You had some of the best theatric minds in the nation come together and craft this tale from a pool of over 200 interviews, representing probably more perspectives than we can even imagine. And they're all writers. They are "writing" this story of multiple voices. And when you get that many good writers with strong, narrative minds at work, seeing patterns, themes and ideas they want to promote... the result is going to be a heavily manicured text no matter what.

You can't turn nine horticulturists with clippers loose on a wild hedge without expecting to get something very beautiful-- and heavily domesticated-- when they're done. That's sort of how I feel about The Laramie Project at the moment, which, when you think about what the hell this play is actually like is a bizarre statement. And yet, I still say that this baggy, multi-vocal play is just too well-groomed. The wildness for which this play is praised is mostly on the surface, and when you strip away that surface, you see its fine architecture and German-made precision engineering purring away on the inside.

You can't turn nine horticulturists with clippers loose on a wild hedge without expecting to get something very beautiful-- and heavily domesticated-- when they're done. That's sort of how I feel about The Laramie Project at the moment, which, when you think about what the hell this play is actually like is a bizarre statement. And yet, I still say that this baggy, multi-vocal play is just too well-groomed. The wildness for which this play is praised is mostly on the surface, and when you strip away that surface, you see its fine architecture and German-made precision engineering purring away on the inside. In another sense, however, I do think that this is a legitimate gripe on my part. Since Laramie residents have only really had a chance to speak out about their experiences through TLP, this is the narrative through which others see them, and perhaps, this is a narrative in which they could just as easily feel trapped. (I can only speak from my own experience on that point.) Furthermore, when this play tries way too freaking hard to push a cleaned-up narrative structure that flattens out the complications and cleans up the activist waters a little bit, we don't get to seem a full, or as complicated, as we really are. And the circumstances around this tragedy don't get to be as rich as maybe they could be, either.

All I know is that sorting through all of this on my own without a guide, twelve years after a friend-of-a-friend I never met was murdered, has been extremely beneficial for the screwed-up eighteen year old who didn't have the chance to sort things out when it was all happening. And I now wonder if keeping things less neat, without an overarching narrative "mold" to make things fit a predetermined version of events, would give others that same experience.

Related Posts:

The Airing of Grievances, Charge 2 cont.

Scatter Plots (this is the first of a short series, and looks at different angles)

The Second Casualty is the Truth

Failure to Engage: the Robbery Motive (Please allow me the grace to be wrong now and then...)

Sources:

Malan, Waynand. TRC South Africa Report Minority Position. TRC South Africa Report, vol. 6. Cape Town: Juta and Co. Ltd., 2003.

Wangh, Stephen."Revenge and Forgiveness in Laramie, Wyoming." Psychoanalytic Dialogues 15.1 (2005): 1-16.

PHOTO CREDIT:

1) Detail of a 1998-99 production of Angels in America staged by the University of Minnesota Dept. of Theatre Arts and Dance, courtesy of the UMTAD Flickr Photostream. (You can see pics of their 2005 production of The Laramie Project here, too.) Available through a Creative Commons license.

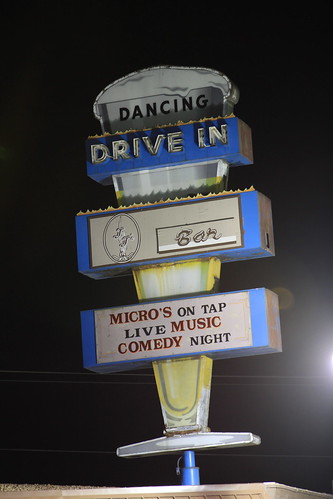

2) The now-defunct Fireside sign, by me.

3) Some awesome topiaries, taken from baralbion's Flickr Photostream. Available through a Creative Commons 2.0 license.

No comments:

Post a Comment