As is pretty obvious at this point, I am fascinated by memory and how people create their sense of identity from their experiences. When I teach my research course here at the university, we use autobiographical memory as a theme that we study and learn research techniques about. In particular, we spend time learning about how frail memory actually is, and how those memories we use to define ourselves get molded to fit how we see the world. If you look at the two previous blog series about my own memories of this event, that's really clear, too: my memory is riddled with inconsistencies which are often dictated by the stories I want to tell-- or want to hide-- about who I think I am.

As is pretty obvious at this point, I am fascinated by memory and how people create their sense of identity from their experiences. When I teach my research course here at the university, we use autobiographical memory as a theme that we study and learn research techniques about. In particular, we spend time learning about how frail memory actually is, and how those memories we use to define ourselves get molded to fit how we see the world. If you look at the two previous blog series about my own memories of this event, that's really clear, too: my memory is riddled with inconsistencies which are often dictated by the stories I want to tell-- or want to hide-- about who I think I am.No memory can be told without a narrative, but the contingencies of storytelling-- of audience, of intent, overall meaning, interpretation-- will invariably rework the material of memory into something else, something with a different texture than before. And those who listen must take that narrative and reverse-engineer it to glean information, to re-create an idea of what that original, "pristine" memory once looked like. They try to flatten out the textures of memory to make it what it once was. And I think many would argue that such an exercise is folly. Instead of trying to flatten out those textures, a better tack might be to run our fingers over them, feel its knap and inconsistencies as part of their makeup.

But there is also the invisible audience-- the imagined audience on the horizon somewhere-- the narrator's family, colleagues, the new government. And every listener decodes the story in terms of truth. Telling is therefore never neutral, and the selection and ordering try to determine the interpretation.

--Antjie Krog, in Country of My Skull, 107

In my class, we spend a lot of time talking about cognitive literary studies, which is a critical marriage of psychological and biological studies of cognition with literary analysis. In my class, we focus on the limitations of how memory works, and in the first unit they discover the holes in their own memories by exploring a personal memory of their own. By the time we get to The Laramie Project, they know about narrative schemas and common slips of the memory; we've discussed Schacter's "seven sins of memory" and how they can cause distortions in how we recall events. Heck, they've seen the gaps in their own memories, even. And yet, I still marvel that, when we get to The Laramie Project in class, they are so willing to take every person's personal stories as factual representations of forensic reality rather than individual, highly contingent recollections of personal experience.

So, naturally, my response as an educator is to mess with their heads. Just like I poked some holes in my own recollections of events at the time Matt was murdered, I do the same to specific memories in The Laramie Project with the class and watch their naive optimism about the solid reality of memory crumble. For instance, here's a personal recollection I share with my students in the middle of our Laramie Project unit:

I had attended the November 2000 performance of The Laramie Project when Tectonic Theater brought it to Laramie, Wyoming. I was a freshman in Laramie when Matt Shepard was murdered, and like a lot of students on campus, I was curious about how the group would portray an event that we had all lived through two years ago. When I went, the audience was full of people who either were interviewees for the play, or they knew some of the people who were involved. My friend "Andie" and I were in the latter group. I knew most of the people from the college in one way or another; I knew Romaine and Jed, though, from high school speech and drama. "Andie," however, was a Laramie native— she knew Jed, Zubaida, and McKinney and Henderson quite well from school. She and Jed had been attending the same church for years. When we got to the theater, the audience was already fairly packed; I found a seat on the far left-hand side of the stage, and "Andie" took a seat directly behind me.

After about twenty minutes into the performance, the actor playing Jed approached the front of the stage and recounted the first time Jed and his parents had a major disagreement over the subject of homosexuality. In the middle of the scene, the actor spoke these lines:

“And when the time came I told my mom and dad so that they would come to the competition. Now you have to understand, my parents go to everything—every ball game, every hockey game—everything I’ve ever done. And they brought me into their room and told me that if I did that scene, that they would not come to see me in the competition… they felt that strongly about it that they didn’t want to come see their son do probably the most important thing he’d done to that point in his life” (12).At that point, "Andie" leaned over and socked me in the arm.

“Pssst— hey, Jackrabbit!” she hissed. I leaned back to talk to her.

“Huh? What?” I asked.

“That’s not true,” she whispered.

“What? What’s not true?”

“That his parents came to everything. They missed tons of stuff because they work odd hours. Especially sports." My eyes popped open in surprise. “You’re sure?” I asked her. She jerked her head back and nodded.

“Yeah. We did a lot of that stuff together. His parents simply did not show up to everything.”

Needless to say, I was surprised at first because of the implications: as far as I could tell, that meant that Jed willfully stretched the truth or simply didn’t remember correctly, or that "Andie" was wrong. I knew both "Andie" and Jed well enough, and I wasn’t willing at the time to pick between them—so I kept my thoughts to myself and didn’t argue the point.

That wasn’t the only time that "Andie" punched me in the arm to point out discrepancies, either— she distinctly remembered several events differently from the interviewees in the play.

Watching my students read this passage is extremely entertaining, in a sadistic sort of way; they start to fidget about two minutes in, and by the time they finish reading that passage, some of my freshmen are positively squirming.

"So," I ask them, "What are your reactions to this?" I usually don't get an answer, so I'll press, "Does this matter to meaning of the play?" Eventually somebody ventures a comment.At this point, there's usually a few freshman grumbling off to one side-- my snarky, combative students, the ones I can trust to take the next interpretive leap. One student raises her hand.

"Well, yeah, he's lying," one student responds. "These guys want to change hate crime laws because of this story, and we can't trust what even Jed says."

"He's not lying," someone else will counter. "Maybe he's just... exaggerating."

"He's not doing either," one girl snaps back. "It's not that his parents came to everything that's important. It's that this is the first time they refused to come see him in something. That's a big difference."

"But that's not what he says," the first kid insists. "He says they came to everything. It's not true."

"But why would he remember all the times they couldn't see him in a hockey game and feel disappointed? That's not going to stick out. What sticks out for him is the first time they didn't want to come."

"So, is he just not remembering right or stretching the truth, then?"

"Um, not to be a pain," she says, " but why should we trust that 'Andie' remembers this event any better than Jed Schultz does? We don't know her. What if she has some kind of ulterior motive?""Okay," I tell them, "now you're catching on. You really have no way of telling who's got the story right. What do we do with three competing versions of the same memory? Why doesn't Jed's or "Andie's" stories line up? For that matter, why trust mine? How, then, do we navigate between them and pick the 'right' one-- or should we?" What then follows is a careful scrutiny of how we decide what details we recall every time our memories become stories, how they get colored, which memories we suppress, and how at the end of the day, sometimes nobody's version of events lines up, but everyone is still telling the truth. We slowly start talking about how the truth of memories lies not so much with their objective reality as their cohesiveness as a narrative: we get to the idea that memory truth is often story truth. And in this case, maybe "Andie" and Jed are telling two different stories rather than getting things wrong.

"Yeah, she went to the same church as Jed," someone else says, "and maybe she's just mad about how Jed talks about it. How can we trust her?"

"For that matter, Jackrabbit," somebody else adds, "why should we believe you?" That first student, the one ready to reject Jed's testimony, leans back in shock. This had apparently never occurred to him. I look around the room and see that same look of confusion on most of the other faces. Objective accomplished.

Is this little exercise a little unfair to pull on a bunch of freshmen? Maybe-- but it points out something critical about how we create meaning out of memories: we have to approach them as stories, and as such we usually do so with a little suspension of disbelief. When we create meaning out of our lived experiences, we have to trust that the narratives we tell ourselves about our memories are the factual truth. Most of my students resist this collapse of truth into narrative; nobody wants to think that our reality is determined by stories rather than facts. And yet, it's our perception of reality-- or in our case, Jed Schultz' perception, or Reggie Fluty's, or Sherry Johnson's-- that steers our lives, our identities, our perception of right and wrong. And those memories of this event are just as frail or subject to alteration as Jed's-- or Aaron McKinney's.

Or mine.

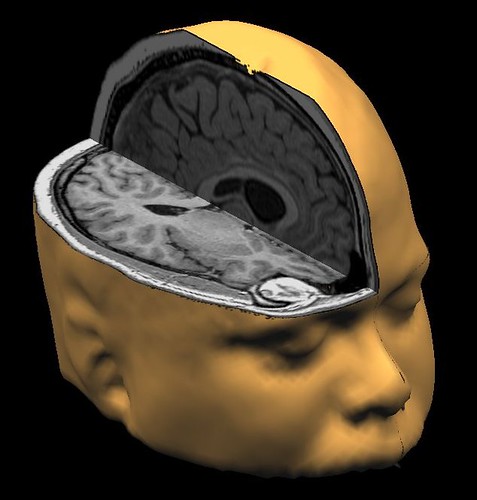

PHOTO CREDIT: Brain scan, by Digital Shotgun, from his Flickr photostream.

No comments:

Post a Comment